Ethel Johnson Author of Draw Me a Tree Torrent

by E. P. Richardson

MR. WYETH," said a New York painter to him, "I enjoy your work very much. I like it at a distance, but when I come near I am always disappointed to see that there are objects."

Andrew Wyeth paints with a brilliance and authority that have imposed him upon an art world preoccupied by ideas diametrically opposed to his own. Art criticism in our time tends to be dogmatic and rigid rather than flexible and receptive. Twentieth-century theory says that this is the age of abstraction, that the observation of nature is finished as a source of painting; therefore, an artist like Wyeth has no right to exist. As one of the most articulate spokesmen of the New York school, Professor Sam Hunter of Brandeis University, put it in the catalogue of the Seattle World's Fair, 1962, "In view of the achievements of the Abstract Expressionists in the Fifties it is no longer possible to assume that the opposing currents of realism, expressionism, a traditional romanticism and abstraction are of equal validity." There is, he said, no valid work independent of the New York school's "formal and ideological preoccupations."

Wyeth causes difficulty, however, even for many of his admirers. He is an extremely well-known and popular painter. A series of exhibitions since the age of twenty and frequent reproduction have made his works familiar to a wide audience; yet misunderstandings are oddly mixed with admiration. Some, like the New York painter, find his work too real; others who enjoy his reality find it sad, lonely, lacking in color.

This disturbing, challenging quality in his work is perhaps the source of an atmosphere of legend that has grown up about him — a curious legend, because it is composed of negatives yet is admiring. He never goes anywhere; never takes part in artists' life; never goes to openings of exhibits or studio parties where artists gather; never travels; never went to school; has never been to Europe; never this, never that. Yet out of all these negatives has come an art whose impact upon the consciousness of his fellow countrymen is positive, by any standard. When the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo held an exhibition of his work in 1962, a quarter of a million people visited it in six weeks. Connoisseurs and country gentlemen, politicians and museum curators, housewives and Hollywood actors, all form part of his audience. When a selection of his drawings and studies were shown in the Pierpont Morgan Library, they held their own in decision and authority in that august company.

I am not a realist at all. The subject is unimportant.

In the roaring torrent of words and images which in this age of publicity pours upon our consciousness at each moment of our lives, the condition of independence is some degree of self-controlled solitude. Wyeth has maintained his independence by living outside the major colonies of artists. He passes his life between Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, in winter and Cushing, Maine, in summer. He was born in the one and has spent nearly every summer of his memory in the other. His work is deeply engaged with the landscape and people of these two tiny hamlets.

The islands and peninsulas of the Maine coast, with its spruce forests and tidal rivers, its unpainted houses, and hayfields forgotten among the spruce woods, have an intense meaning for countless thousands of Americans, blended of memories of childhood holidays and of the remarkable character of the landscape itself.

Chadds Ford in Pennsylvania is, on the contrary, in a virtually unknown part of our world. Between the Delaware and the Susquehanna rivers the rolling piedmont upland pushes down to within sight of tidewater. One can look out from hilltops three hundred feet above sea level to see the sun shining on the great bays into which the ships bring the iron ore and the oil of twentieth-century industry. In the eighteenth century the Brandywine. which finds its way down over ledges of granite through those hills, was the seat of one of the great industrial complexes in the American colonies: it had waterpower and water transportation; iron ore in the hills, and wool and wheat on their fertile surfaces.

The tobacco culture of Chesapeake Bay never penetrated those hills. The Dutch (who called the Delaware the South River), the Swedes, and the English Quakers who settled there built forges and water mills instead of plantation houses. Like good Netherlander and Englishmen, they built their towns of brick, but their mills and forges and houses in the countryside were made of the gray-brown stone of the hills. Countless numbers of these stone buildings still stand, forming one of the beautiful regional architectures of the United States. What they look like, and how integral a part of the hills they seem in winter months, when Wyeth is in Chadds Ford, you can best see in his pictures.

I confess that I, too. approached his work with a misunderstanding. The haunting eloquence of his works, especially of the last decade, has a very strong attraction for me. It deals with people and places of strong and distinctive character. The spruce woods and tidal bays of Maine are part of my own memories. Chadds Ford, five miles from where I now live, in the months of January to March looks everywhere like a Wyeth, and each bend of the road brings the pleasure of recognition. Its bare fields and stone buildings give a sense of the past flowing into and mingling with the present that is not often so vividly felt in the landscape of North America.

Wyeth lives in a mill which he has recently bought, a mile or two up the Brandywine from his former home. I first saw this mill in a driving snowstorm. The snowflakes swirling around the massive stone walls, the silence of the storm, and the inkblack waters of the millrace made an unforgettable impression. The mill was built in the early eighteenth century. Gunfire of part of the Battle of the Brandywine rattled around it, but the Quaker miller, true to his principles, left that day blank in the mill's daybook rather than mention the fighting.

The mill walls stand firmly, though water rushes through an empty hole where the wheel once was and the interior is a ruin. The Wyeths were living at first in what had been the granary, which they rebuilt and occupied while the miller's house was being reconstructed. What had been, shortly before, a ruin open to the sky had become a home, warm, sweet with the smell of the wood fire and the Christmas tree; behind the Christmas tree one could read a name and numbers scratched on the plaster by an eighteenth-century miller. Last fall they were in the house itself, which Mrs. Wyeth has reconstructed inside with love and great taste. The low-ceilinged rooms with white plaster walls are furnished with Chester County furniture, whose combination of rustic strength and elegance I find very appealing; as in an Italian house, a few good pieces fill and furnish a room.

Circumstances had taken my wife and myself to Rome last autumn. We were talking there one night at dinner about Wyeth's art. We had been to see a sculptor. Giacomo Manzù, who lives in the summer months in a tomb on the Appian Way. In what had been a farmhouse hidden within the superstructure of the vast, round, fortresslike mass of the tomb was a charming modern villa, from whose windows we looked out upon the brown Campagna and the avenue of tombs and pines stretching off toward Rome in the distance. The Campagna, like a battlefield or a place which once was sacred, is haunted: it is a place where one feels alone, yet not alone, for a sense of something once present and now gone hangs in the air. It made me think of the mood of Wyeth's Chester County. Was this what he saw in his subjects and made me feel so strongly in his work?

"Tell me about Chester County," I asked him when we returned. "Why is it so important to you?" He looked a little puzzled. "I love the name, Chester County. But I've only lived in it two years. The house on the other side of Chadds Ford where I was born, where we lived until we moved into this house, Brinton's Mill, is in Delaware County. But they were all one, originally." To make my question clearer, as I thought, I spoke of the quality of the landscape around Chadds Ford, which all feels to me like the quiet fields around the stone Quaker meetinghouse where the Battle of the Brandywine took place, and of how the sense of the past permeates it everywhere.

"I don't have much feeling for the past," he said. "My feeling for history is not connected with dates: it is the way the landscape looks in the moonlight." He paused a moment. The image of moonlight on the brown fields outside evidently turned his thoughts to a matter on which he felt a strong need to defend or explain himself.

"I have been criticized greatly for the lack of color in my work," he burst out. "My father used to say to me, 'Andy, use more color.' It was not my father so much as the people in the commercial field with him who criticized my lack of color; this bothered him, so he kept after me about it, although I think it was his friends' criticism rather than his own.

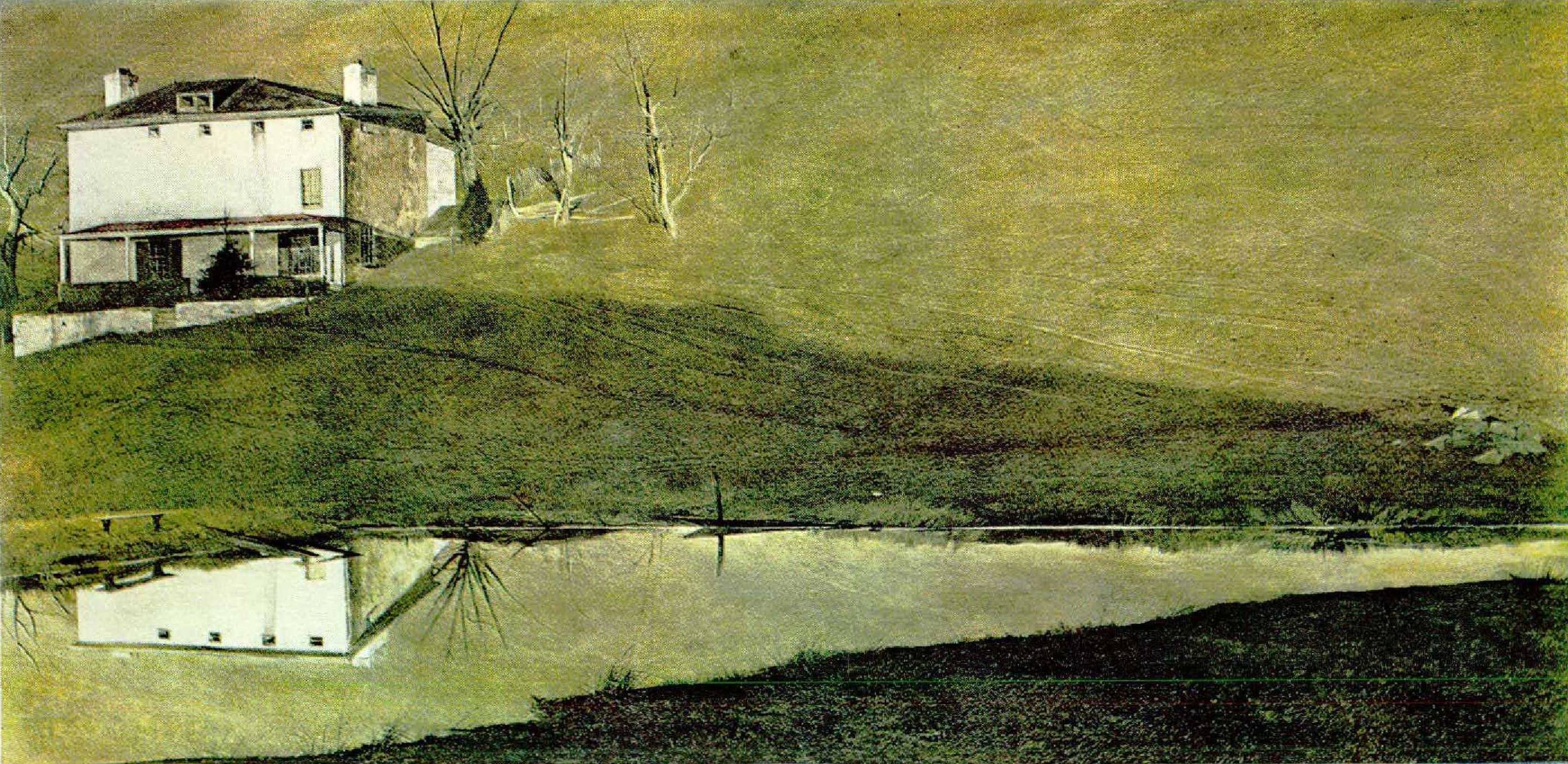

"Do you remember a picture in the Buffalo exhibition called Brown Swiss? It is just a house in some fields. The whole picture is mud color. I don't consider myself particularly an artist, so far as picking a color to paint; my color is organic; it is simply part of me. I saw that house once in just that light and wanted to paint it. I remembered the miller who lived there and how he used to come to the door, when I went there as a child, all covered with flour dust, all one color except his eyes, which were reddened by the dust. My reason for painting it was just that tone, that light."

Far from being troubled by this aspect of his work, I explained, I enjoyed it. I hold an unfashionable opinion that the French Impressionists painted beautiful pictures; yet because they eliminated the range of tone — that is, light and dark — and relied instead upon variety of hue — the color spectrum — their effect had been to impoverish the language of painting. Their influence had, I thought, put painting since that time on the wrong track, and it pleased me to see a painter once again use a rich range of tone and simple scale of hue, as painters had done from the time of Bellini and Titian to the middle of the nineteenth century. This unorthodox opinion seemed to surprise and please him.

But I still wanted to understand his relationship to his two subjects, Maine and the country around Chadds Ford. Why just these two, Chester County and Maine?

He hesitated a moment and his wife, Betsy, observed, "Why, you have often said to me, 'This is all I have room for in my heart.' "

"All I know," he said after a pause, "is that I am not a realist at all. This was brought to a focus for me by the death of my father. It was a tragic death; he was killed at a railroad crossing near his home. My difficulty — and my great urge — is that subject is unimportant. The less there is in the subject, the more I can pour myself into it. The familiar frees me. If I go to a place with marvelous settings, I am caught — caught by the object. I take pleasure in other landscapes, but I don't have any personal need to release it.

"Now that picture" — pointing to The Trodden Weed, two booted feet tramping across brown grass — "is not a great picture, but to me it has something to do with my father. I never painted his face, but I have done some things more like my father than if I had done his portrait. When I was a child I used to go into his studio, which is still there, over at the other house. The vestibule, I remember, was always cold; and a couple of prints, snowy landscapes of Switzerland, hung in it." (Andy's grandmother was Swiss; she was the daughter of one of Agassiz's assistants, I learned later.) "You see a patch of snow in the background of that picture? To me it is all based on the experience of that cold, damp room."

Caught by the object

I was curious to know what he meant by this phrase. "I have a very strong feeling," he explained, "that the more objects you use, the less there is in the picture. Robert Frost is deeper than his New England subjects. I have painted old farm wagons and things like that, but I think this is the weakest part of my work."

At this I put in a word in defense of his old wagons. Things used by men, old and worn by use, take on a life and personality which, I said, he painted with remarkable eloquence. "Oh, I never doubt the object; I doubt the way I paint it. You know, I have imitators who seem to me to be just painting objects. This is the weakest part of me.

"I must have some personal experience of a thing. This past fall, in Maine, Betsy had placed a pumpkin on top of a post in our lane. I used to walk up that lane every morning to have breakfast with Betsy's father. He was dying of cancer; I had breakfast with him every day, and we had wonderful talks. One day as I walked by, that pumpkin suddenly expressed to me all the falls I could remember. As a child I was alone a lot; I used to walk in the fields where there were pumpkins. I used to make jack-o'-lanterns; sometimes I cut them in the fields. I remember the smell of a pumpkin when you cut it open."

Abruptly, he left the room, and returned bringing a large water color. It represented a pumpkin on top of a weathered fence post rising from a tumbled stone wall. The orange pumpkin gleamed in light against a dark background which suggested without describing a woodland.

"I don't pick a subject because I think it will be an effective composition. What I wanted was to express the strange waxy surface of the pumpkin; the pungent smell; the post, too, was a wonderful, organic thing. I painted that in two afternoons; I went back the second afternoon to get some of the textures I wanted. But when I think of it, I don't remember the painting, or the planning of it as a picture. I remember the smell of the spruce woods behind. Perhaps I was thinking, too, of the smell of pumpkins. I wanted to express the sadness of this fall, and how there were other pumpkins in all the farms around. A chipmunk lived in that wall. We always called him George. When I showed the picture to my father-in-law and talked to him about what I should call it, he said, 'Why not call it George's place?' So, George's Place it is."

It was becoming clear to me as he talked that the aura of memory which is so strong in Wyeth's pictures is not an element observed in the subject and painted by him; it is a feeling in the artist himself, intensely felt and powerfully expressed in a mysterious but cogent way through the subject.

I am a fanatic about painting. Nothing means anything to me but painting.... If I were taken to another part of the country which I didn't know, I doubt if I could paint anymore.

The mingling of memory and observation, of feelings and the objects which arouse them, is not a new thing in painting: it is as old as the art itself. In our century, however, it has become a rarity. The theories of our time (which is a time of theories) hold observation to be a mechanical copying and consider emotion free to express itself only when it is detached from observation.

I was interested to hear what more Wyeth, who uses observation with wonderful skill yet does not consider himself a realist, would say about this ancient yet forever mysterious paradox of the art of painting.

"I am a fanatic about painting," he said. "Nothing means anything to me but painting. But just to put down tones doesn't excite me. It gets to be a cliché, a mannerism."

I reminded him that Leonardo da Vinci had written of how the art continually declines and deteriorates from age to age when painters have no other standard but the works of others. Wyeth agreed with this. "Mannerisms take over when you cut yourself off from nature," he said.

"I don't know — if I were taken to another part of the country which I didn't know, I doubt if I could paint anymore. I am excited by tone, but I have to have a feeling first. Do you remember a picture I did of a blueberry box and an enameled cup in the grass? I called it A Quart and a Half. I had been painting my wife asleep in the grass [Distant Thunder, 1961], It was a big tempera, and I had worked on it a long time. Then she went away; came down here to open the house. I went out the next day and saw the cup, which her mother had given her, and the blueberry box still there in the grass, just as she had left them. It struck me so that I painted the picture."

My father taught me remarkable things, but not only in the studio—just living with him.

The education of painters today tends to come much later in life than it once did. It is often forgotten, too, that painting is a craft as well as an art, and, moreover, a difficult craft. The apprentice system which gave the artist his training in earlier centuries took a boy in his early youth and made him learn his skill from the ground up, not only drawing and painting but grinding colors, preparing canvas, and learning every other part of the artist's craft. Painting, considered as a skill, involves two things: dexterity in handling certain tools and control of the hand to make it do exactly what the mind wishes to do; and knowledge of materials and processes, each of which has its own possibilities and limitations.

The ready-made artists' materials invented in the nineteenth century enabled painters to do without knowledge of their materials. In our time the training of the artist has come to be considered a training of the mind rather than of the hand and arrives later and later in life: some artists begin painting after getting a Ph.D. degree from a university, or even after reaching the age of retirement; in either case, it is too late to achieve an exact muscular control of the hand.

Wyeth is a very rare instance today of an artist who was trained in the studio, from childhood, by his painter father. A delicate child, the youngest of the family, he was never sent to school but educated at home. His father was severely criticized then, as Andrew Wyeth is criticized now for following the same system of home education for his son Jamie. But he believes that artists are at their most open stages of development between the ages of six and sixteen and should not be shut up in a room all that time.

In Wyeth's case there was no lack of discipline. His father gave him the strict training of the old academies: first, drawing in charcoal from casts; then, when the boy had achieved a certain proficiency, drawing from the model, and the study of William Rimmer's Anatomy. "He would have me make drawings from the model, then turn my back and draw it from memory. But he never talked about technique. 'Andy,'he said to me. 'I want you to learn to draw so that when you want to express yourself, you won't fumble.'

While the son was in training, his father was at work in the next room as a busy, successful illustrator and mural painter. The boy learned more by observing, as boys will, than from actual teaching; his schooling was, in fact, an apprenticeship, an important and normal form of education three hundred years ago, but today hardly more than a word in the dictionary. "My father taught me remarkable things, not only in the studio but just living with him. He didn't put fences around me. He gave me the appetite for looking deeper, made me see the depth of an object. He made me paint still life, and would say to me, 'When you re doing that form and shadow, remember it is not just a shadow. It is something that will never happen again just like that. Try to get that quality, that fleeting character of the thing.' "

"The remarkable thing about Andy and his father," said his wife, Betsy, "was the lack of rebellion."

"We believed absolutely the same things, but we went about it in a different way," was her husband's comment. "He was far from a simple man. He thought a great deal about art. My father was going through a terrific transition in the period when I was forming. He was studying Cézanne and the modern French. He painted many abstractions toward the end of his life. He got to know Christian Brinton, who wrote books on Zuloaga and on the Russian moderns of that time. Brinton used to bring European painters clown to see him. My father told me that one Russian painter said to him, 'Mr. Wyeth, there is too much painting in your work to be good illustration, and too much illustration to be good painting.' This kind of thing shook him. The trouble was that everything he did was from imagination, not from nature; and this left him open to attack, and made him falter. At the end, though, he swung back to believe in what he had originally believed in."

Anyone who paints objects is in a very dangerous position.

Wyeth had his first exhibition of water colors at the age of twenty, at the Macbeth Gallery; and he always speaks of its proprietor. Robert McIntyre, with great affection and respect. Those who remember his early work can appreciate what a long road he has traveled. His youthful water colors were almost explosively emotional, quick and dramatic responses to nature. When Peter Hurd, thirteen years older than Wyeth, came to study at Chadds Ford with N. C. Wyeth, and eventually to marry Andrew's painter-sister Henriette, he taught the boy to use both tempera and fresco. Something in Andrew Wyeth's nature responded to tempera painting — he liked its dryness, its precision, its possibilities of effects both of depth and strong pattern. He began to work in tempera in a new direction which did not please his admirers.

We had been talking about the combination of freedom and control which his work now shows to an extraordinary degree. "I agree with Pollock, and Kline, and de Kooning that there must be no laws: there must be complete freedom. But they lack the object. I'd like to have the effect of complete freedom, but I also want the object. I'd like to paint the thing just as it might happen to look as you walked by. I don't mean a snapshot; it's more than just a glimpse — but I love that quality of the unexpected."I remarked that you can only do this if you have such complete control of your technique that you can forget it and think only of what you wish to say. "Oh, yes."he said, "I believe in discipline." Pointing to the portrait of Nicky on the wall, "Howard De Vree once told me to my face that I was wasting my time to do this kind of thing. He ripped me apart in his review and said it to my face in the gallery. He loved the freedom of my early water colors and thought I would lose it all. I was trying to learn to draw. The whole reason for doing so was to get freedom and this other thing."

"Does it bother you when people take your love of objects as lack of imagination and think you are just painting the old oaken bucket?" I asked.

"No, no. Anyone who paints objects is in a very dangerous position. When I am misunderstood, I think I have failed. I never have any doubt about the object; I doubt the way I have done it."

Sad? I don't know why.

Why do you think, I asked, that so many people think your work is sad?

"Sad? I don't know why, I'm not sad. Perhaps they think so because it is low in key. People confuse dark color with sadness. Unless your work is calendar color, it disturbs them.

"I think they're fearful of the dark. Robert Frost strikes people the same way. I get many letters from women who grew up in the country. My work seems to remind them of the way the world used to be; and they are sorry their children cannot have the experience they remember. I believe people think my work is sad because they are afraid of solitude and silence. I love to be by myself."

The danger of anything closely done is that people feel that the technical means are the end of the thing. That's just the beginning. A picture is not like a piece of jewelry.

The artist who wishes to observe and to use observation today as a vehicle of the imagination has a long and solitary road to travel. There are such artists. Our civilization is woven of many strands, not one only, and there are, and always will be, artists whose material is the outer world and who wish to see, as Edith Hamilton said of the Greek poets, "the things men live with, noted as men of reason note them, not slurred over or evaded, not idealized away from actuality, and then perceived as beautiful."But Andrew Wyeth is the only one of these artists who has forced his acceptance as a modern master by critical opinion in spite of the prevailing mental climate of our time; and even his art is widely misunderstood.

"The danger of anything closely done," he once remarked, "is that people feel that the technical means are the end of the thing. That's just the beginning. A picture is not like a piece of jewelry."

As a boy, Wyeth admired Howard Pyle's illustrations. His father had studied with Pyle and owned not only his illustrated books but a number of his originals. The boy's interest was both in the romantic appeal of the illustrations for a twelveyear-old and, as he says, in a certain truth and technical clarity that Pyle stood for. When about seventeen, Wyeth discovered Winslow Homer, whose water colors appealed to him greatly. Then came the discovery of tempera, taught him by Peter Hurd, and a dissatisfaction with the wild expressionism of his early water colors. Two old masters also taught him. The first was Dürer, whose water-color drawings had a strong influence, due probably, as he says, to their textures, which he wanted to get in his tempera. A later influence was Rembrandt's drawings. "My father was a great lover of Rembrandt and had books of Rembrandt's drawings in his library. But with me it was a kind of natural uncovering of Rembrandt's drawings. I loved the richness and the mystery of them."

It was also characteristic of these artists to approach their work by way of intense preliminary study. Since his father's violent and tragic death turned Wyeth to the emotional side of realism, he has also developed a method of work which enables him to combine the spontaneity of the first glimpse with the sustained, easy power of a highly disciplined talent in action. He is basically an outdoor painter: that is, he works from nature, and the beginning of each picture is a fresh personal experience. This is often a momentary effect of light catching and transfiguring a familiar object. He does quantities of quick brush drawings of such fleeting moments in the life of nature; these serve to put down very directly and hold the experience that excited him. The subject may be hardly recognizable in these first studies.

Sometimes such a study will be all that he does; sometimes, looking over these studies afterward, he will find that he wants to develop an idea into a picture. In this case, he will go back and do many more studies, a dozen, two dozen perhaps, giving each element its own intense scrutiny, until the whole falls into place in his mind and he knows every detail by heart, before painting it. But the goal is always to achieve the effect of that first momentary flash of excitement and delight. "I hate composed pictures," he says. The quality of a momentary shock of recognition, but expressed with the clarity of deeply considered understanding and with the power of a highly trained instrument of expression, is not easily arrived at. Chardin once quoted a painter friend Lemoyne as saying that "one needed thirty years of practice to know how to keep the qualities of a sketch." Wyeth has achieved that quality today: the combination of perfect freedom and exact control is one of the most distinctive things about his art.

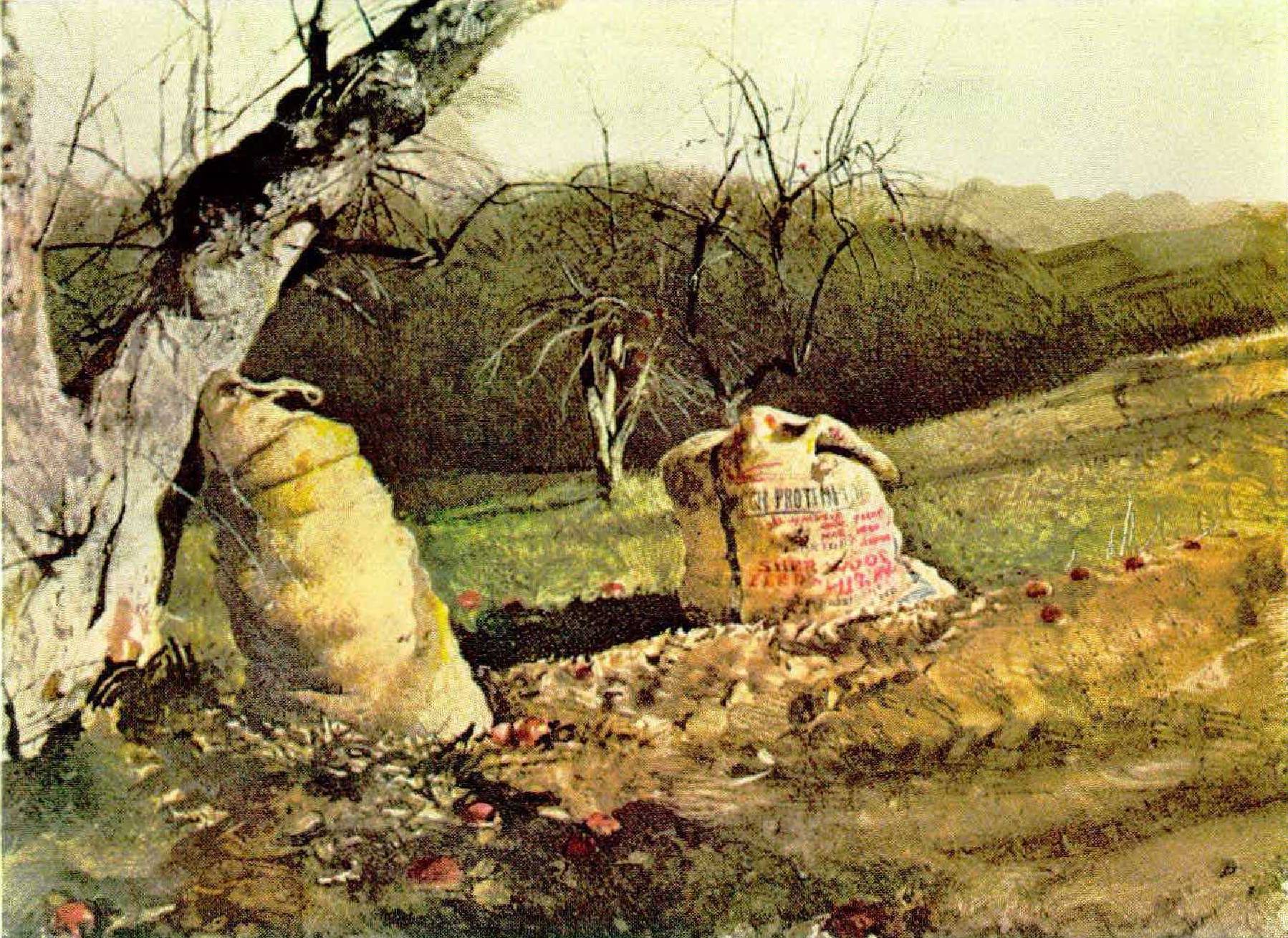

An example. The germ of Brown Swiss was the gleam of light on a white wall against the tanbrown earth. Wyeth put this down in quick sketch, as free and emotional as his first water colors. Between this first quick note and the finished picture came twenty or thirty drawings: the house from various angles; the cattle which were standing in the foreground and which disappeared, except for their name, from the final work; even a deer hanging by a rope from one of the trees, which also does not appear.

A more recent example is a picture called Adam. Adam Johnson, an old Negro farmer who lives just over the hill from Wyeth's studio, has been the subject of many of Andy's pictures. The bond of friendship between the two is deep and usually unspoken, but once Adam said, "I feel about you as a brother, Andy." Wyeth has painted many subjects around Adam's farm and goes there often on his walks.

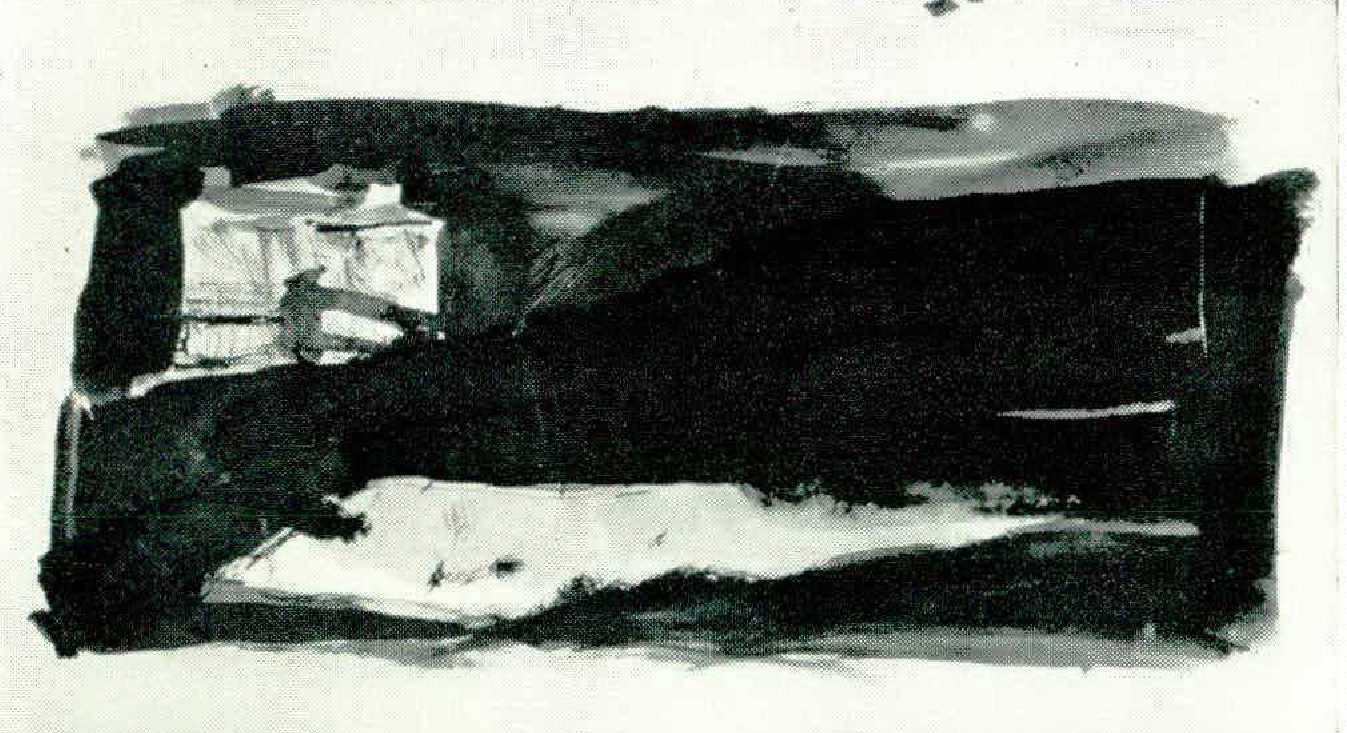

One afternoon in late winter, getting on toward spring, he found Adam cleaning out his pigpen, getting it ready for a new litter. The old man, who is very deaf now, did not hear Wyeth's approach but came slowly down the slope, a frown of concentration on his face. The evening light glowed on the faded blue of Adam's country clothes and on the bleached boards of the pigpen, and a flock of starlings flew like black arrowheads up into the sky: that was the moment of experience. Wyeth made the water-color sketch of it reproduced here.

About a month and a half later, looking at the sketch in the studio, he thought there was something grand and elemental about the old man's figure. Although he had painted both man and place many times before, he went back and made perhaps twenty-five careful studies — of Adam's face, his clothes, the boards of the ramshackle pigpen, a post at the right, an overturned tin pan; how a piece of burlap was tacked across a gap in the boards — from various directions and at different times. "I like to move around, look at the thing from all directions. It's what seeps in from the object unconsciously that concerns me. I keep these drawings around, not to copy, but they give me warmth. All those shapes of the pigpen — you know how Negroes of that generation put things together. He was a wonderful elemental figure coming toward me out of chaos. That, and the amber light, were the reasons I did it."

Dry brush is a great medium. But I can't control it. And if I can control it, it's no good.

Wyeth's painting style is a dialogue between spontaneity and discipline: between a passion for freedom and immediacy on the one hand, and on the other, a conviction that the wonder of the objects which make up this world can be grasped only by the most painstaking and loving study.

Like a number of notable American painters of the past hundred years, therefore, he finds water color congenial and uses it as a major, not a minor, medium. After the facility of his early water colors (which he looks back upon now as dangerous), he hit upon a method of painting that appealed to him; he calls it dry-brush water color. This is not a unique invention. Fifty years ago, for example, when a great deal of magazine illustration consisted of pen-and-ink drawings, the tool used by illustrators was not a pen but a fine water-color brush, dipped into India ink and drawn to a fine point between the fingers, or on a rag, squeezing out the excess ink in the process. A fine-pointed brush could draw as delicate a line as a crow-quill pen, yet it had a flexibility of stroke which no pen could give, or, with a dip of the brush, could turn into a thunderous wash.

Wyeth fell accidentally upon this combination of drawing and painting in water color. A picture called Faraway (1952) ol his son Jamie in a coonskin cap, he considers his earliest use of dry brush in a painting that satisfied him and which he allowed to be exhibited; but the technique is so natural an expression of his temperament that it must have been long germinating. Dry-brush water color can be done either out of doors or in the studio. He considers it his most natural and spontaneous medium and speaks of it simply as "carrying water color a little farther." It seldom happens that he does not use both dry and wet brush together.

I complained to him a little about the things listed as dry brush in catalogues of his exhibitions that seemed to me indistinguishable from straight water color. "I know," he said, "people call all sorts of things dry brush that aren't really. The real dry-brush water colors are things like the little Negro girl you saw in the last Whitney annual A Day at the Fair, now in the City Art Museum of St. Louis], or Quaker Ladies, or The Drifter [the remarkable and touching portrait reproduced on the cover], I use both together. It's very important to me to keep things fluid in the beginning. I'm not a careful worker. There are splatters of paint all over my studio. Many pictures remain so nebulous that I can't show them. Dry brush is a great medium. But I can't control it. If I control it. it's no good.

"Artists today," he went on, "think of everything they do as a work of art. It is important to forget about what you are doing — then a work of art may happen." This was a revealing statement from someone who is criticized for the perfection of his technique. Then he said again, "I want to keep the quality of a water color done in twenty minutes but have all the solidity and texture of a painting." Richness of texture within the broad tones of his pictures has become, in fact, as important to Wyeth as the precision of his brushstroke. Unlike most painters, he works over his water colors: sometimes he will use opaque white to give density, or will lift off the color with any means at hand—sandpaper, or the palm of his hand pressed on the wet color — to give transparency. (Anyone who will examine Winslow Homer's apparently direct water colors will find that he also worked over them in all sorts of ways.) And although he says he can't control dry brush, his technique is now at the point of craftsmanship where skill becomes unconscious and the mind concentrates entirely on what it wishes to say.

In contrast to the freshness and spontaneity of his water colors are the paintings in tempera and the precise pencil drawings made as preparatory studies for them. At one time he used to make fullsize, very detailed water-color studies for the tempera pictures, but the preparation he now prefers is pencil. "What kind of pencil?" I asked, thinking of the beautiful silvery quality of those drawings. "Just a regular store pencil, neither soft nor hard. I tried lithographic crayon, but I didn't like its scratchiness. I love the quality ol pencil. It helps me get to the core of a thing, and it doesn't compete with the painting. With pencil I can study things in detail — it gives me the architectural structure — but the color stays like a dream at the back of my mind until I come to paint."

The medium for his most sustained and controlled statements is egg tempera, used on gesso panels just as it was used when Cennino Cennini wrote his description of the technique in fourteenthcentury Florence. It is dry mineral pigment, ground to a fine powder, mixed with yolk of egg and thinned with water. Modern chemical pigments have not yet invaded the ancient technique, at least as Wyeth uses it; his colors are the old earths and minerals. Some he grinds himself; some come from his brother-in-law's ranch in New Mexico; some are from India, or Spain; and he showed me with delight his cobalt blue — ground lapis lazuli from Persia. His palette is the normal shape, but made of metal, with sunken cups, not unlike those of a biscuit pan, around the edge in which the colors can be kept moist; yolk of egg in a glass dish; pure water in another; and fine watercolor brushes. That is all.

Tempera is not a portable medium like water color; it is a slow, patient, detailed technique. "I enjoy having a picture in my studio that I can nibble on, and feel that I can come close to the essential. I don't know whether I can ever master it as I'd like. Not many people have, I believe. Even with Botticelli there is a falling off in his later things, don't you feel? The thing that makes me hang on to tempera is that if a picture does come off, it has a power and a solidity nothing else has; and there's a schematic quality about pure tempera that I like. It doesn't fit into the big shows of today: it's not spontaneous, it doesn't shine like oil, it has a dry substance. But" — his eye lit on a faded blue jacket hanging on the plaster wall — "look at that blue. Nothing else can do the air within that shadow so well as tempera."

The wealth of things around us for an artist to see is just unbelievable. To see it and to clarify it in my own mind. That is the thing.

Wyeth is an articulate person and his own best spokesman about his work. He has such an important talent for the difficult art of painting, his gifts of thought and feeling seem to me so exceptionally interesting and our time so ill-equipped to comprehend the imaginative use of observation, that I have let him so far as possible speak for himself. Good painting, however, like good art of any kind, rises from very deep sources in the human soul, deeper than words can penetrate; and it speaks to the wordless depths of others. To some degree, the observer sees his own reflection in the dark glass; and something always remains unexplainable.

What is very clear, however, is that here is an artist who deliberately and thoughtfully stands aside from the majority trends of today; who has gone back of contemporary art to another, older tradition of painting; and who has reasserted the values of this kind of painting with a mastery and an authority that all must recognize.

I like to think of Andrew Wyeth as I have seen him, leafing through a pile of his quick studies, pausing to look a little longer at this one or at that, saying with an eager note of delight in his voice, "The wealth of things around us for an artist to see is just unbelievable. To see it and clarify it in my own mind. That is the thing."

Coming in the July ATLANTIC

DISTURBED AMERICANS

A Special Supplement on Mental Illness

DR. JOHN H. KNOWLES General Director Massachusetts General Hospital

DR. WILDER PENFIELD Montreal Neurological Hospital

DR. WILLIAM W. SARGANT of London

DR. JAMES A. PAULSEN Chief of Counseling Service Leland Stanford University

DR. PAUL HOCH Commissioner of Mental Hygiene for the State of New York

DR. ROBERT COLES of Boston

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1964/06/andrew-wyeth/658410/

0 Response to "Ethel Johnson Author of Draw Me a Tree Torrent"

Post a Comment